The following interviews were provided in 1999 and 2002 (initially to mark international Year of the Older Persons), and held at Mt Albert Library in two volumes. If you have a story to tell, please send it. Paste it into our email link

Put on your blue suede shoes

Lewis Campbell remembers good times at the Mt Albert Teenage Club between 1957-59 in the now-demolished King George Memorial Hall at the intersection of New North Rd and Mt Albert Rd: “The band or canned music was basically the attraction and in the peak days of rock n’ roll and dance, few teenagers could help but respond to the backbeat.

“In Mt Albert, the Vikings, wearing their red embroidered t-shirts complete with tassels and swish-back hair, were a legend on their own.

“Musicians included Bruce King and Ken Lowe, pianists Lewis Campbell, Denny Behrens and Dick Blundell, guitarists John Neilson and Ray Clarke, saxophonist John Stratford and bass Tuffy Smith. The Coronets vocal group included lead singer Ray Morgan and brothers George and Dave Cowell.

“The moment the band played the floor would be packed. The dancers wore bright colours, string ties, bobby sox, billowing dresses, stove-pipe trousers, pointed shoes, side burns and lots of Brylcreme for the boys.”

Here comes the ice-man

Beryl Basildon, born in 1913, writes of her experiences in the 1920s: “George Moyes and his wife kept a general store, with their home at the rear, in the point of New North Rd and the then Mountain Rd (now Kitenui Ave). Mr Moyes had been blinded and lost some fingers of one hand in a mine explosion. He often sat on an upturned box at the front of the shop. Some of the local men would come and sit beside him, to chat or read the paper to him.

“All our groceries were from there and Mr Moyes did local deliveries, as he knew all the homes nearby. He would carry a wicker basket of groceries on one arm and tap his way with his walking stick along the home frontages.

“Home deliveries were plentiful and the service was excellent. Mr Christmas Davis was our baker. He came (I think) every second day with a great variety of bread – more so than today. He had a most handsome baker’s cart and a spanking black horse. The cart was shining black, heavily scrolled in gold and with his name in red lettering.

“…The iceman came weekly (more often if you were rich), with a huge block of ice balanced on his shoulder and placed the block into the top of the ice-chest. Here it cooled milk and butter and slowly dripped its way to the ice-tray.

“The Herald was delivered by Mr Delugar, by horse and cart from a “Ben Hur” shaped vehicle. The paper was folded, twisted and thrown from the roadway onto the driveway on dry mornings and (hopefully) onto the front verandah on wet days. The price: two pence per copy or nine pence a week.

“The Herald was delivered by Mr Delugar, by horse and cart from a “Ben Hur” shaped vehicle. The paper was folded, twisted and thrown from the roadway onto the driveway on dry mornings and (hopefully) onto the front verandah on wet days. The price: two pence per copy or nine pence a week.

“Gas lights lit the street with a ‘gas-lighter’ who walked the streets at sundown and pulled a switch to switch on the lights and, I presume, did the reverse each morning to switch off.

“One of the wonders and great attractions of the street was the horse trough. The size and shape of a large family bath, it was on the curb side at the foot of ‘Mountain Road’ (Kitenui Ave) opposite Moyes’ store. The water, with automatic filler, was always somewhat green, with wisps of oats, chaff and straw floating – from the horses’ nose bags. How welcome that rest and water was to all those hardworking horses.

“…In 1922, Mt Albert was involved in a serious outbreak of typhoid fever. The borough then had its own water supply, from a spring in the asylum (Carrington) grounds opposite the school (Gladstone). The water was then pumped up to the reservoirs at the top of Mt Albert.

“I understand that the spring became contaminated when the piggeries were moved from below to above the spring. Children and adults went down like flies when the diagnosis of typhoid fever was made. Two wards at Auckland Hospital were soon filled, with over 50 patients in each.

“As a victim, aged 8 years, I still recall going to hospital – three in a two-patient ambulance, one adult on one stretcher and two children, top to tail, on the other, such was the demand for urgent transport. Treatment was mainly palliative. The tough and the lucky survived but many died.”

Playground that turned into retail bustle

Barbara Ashton (Elliott) lived in Cornwallis St, St Luke’s, as a youngster and shares this memory from the 1940s: “Our house backed on to a vast wasteland of huge volcanic rocks covered in fennel, gorse and blackberry, and became a wonderful adventure playground for the local children.

“Picking blackberries in season was always fun and the resulting blackberry pie or jelly a real treat. We also had a hen house at the bottom of the garden and always a good supply of home-grown vegetables.

“Picking blackberries in season was always fun and the resulting blackberry pie or jelly a real treat. We also had a hen house at the bottom of the garden and always a good supply of home-grown vegetables.

“Each Guy Fawkes day a huge bonfire would be attended by all the locals. My younger brother, who was only three when we moved there (in 1939) used to call the area ‘the faraway’ and if he came home smelling fennel we knew where he had been.

“We could never have foreseen that expansive area would one day become the upmarket shopping complex it is today (St Luke’s). When St Luke’s was first proposed in the 1960s the developers, Challenge Properties, came out and sat around the kitchen table with their plans and research figures, and so it began.

“Eventually my father represented the residents of Cornwallis St in their fight for a better deal from the developers. This was finally achieved without legal representation – quite a victory! Imagine that happening today!”

Ernie the rat catcher

Colin Clark and his family moved to Mt Albert in 1934, living in Rossmay Terrace next to KDV timber yard, and he writes of that interesting environment: “It was a great adventure playground for boys. Large rats lived in the area. Volcanic rock allowed them to have many tunnels, especially around our home. We caught them quite fine in wire cage traps.

“We had a black spaniel, Ernie, and next door lived Digger, the Culley family dog, a brown and white Roxie. We would take a rat in its trap and the dogs to the road… Digger on one grass verge, Ernie on the other. On opening the trap door it was GO! The race was on.

“Ernie invariably won. On catching the rat he would toss it in the air with a flick, breaking its neck, back or whatever, and walk away. On its landing, the rat was dead. Digger would pick it up, parade with it and then take it home.

“Once my dad brought some carbide home. We put it down the holes and added water to fumigate the rats. One evening, another lad, John Thorburn, and I poured carbide into holes by the timber stacks on the road verge. We wonder what would happen if we put a lighted match to it.

“We stood well back, threw down a match – and bang! Wow! What a bang. The road shook…we never revealed what we did and never dared do that again!”

A woman’s place where hands were never idle

A. Cooper vividly remembers holidays with Gran Margaret White and Poppy Wilfred White (Allendale Rd residents from 1919-1962): “Gran’s room was across the hall with its runner carpet down the middle. Gran’s room had white lace curtains and white lace covers on the bed. It smelled of lavender with strange florally things in lace-covered bags hanging in her wardrobe.

“She had matching hair brushes and a hand mirror next to her handkerchief box. Another silver box with her jewellery in it also sat on the large mirrored dressing table. Hand tatted doilies sat underneath each one.

“Her lawn nightie with handmade lace and ribbons was in a lace bag on the bed. On top of the bag a quilted cat sat.

“Gandpa’s side had his checked pyjamas and on the brass hook next to the wardrobe were his velvet smoking jacket and dressing gown with its gold tassels on the girdle.

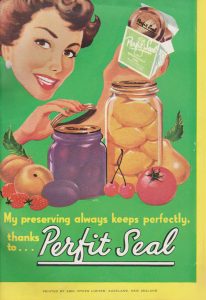

“When my parents and sisters visited too, I slept upstairs in the box room on a camp stretcher. There among the jars of preserves lined up on the shelves, the metal boxes of old, bearing names like a travel-log of places visited but not forgotten – the memories of my grandparents’ journey from England to New Zealand were in place forever.

“The room had a soft light from the window… and the smell was comforting and familiar.

“Downstairs the kitchen was the centre of baking and bustle. Unless they were eating at the linen-set table, men merely passed through and never stayed to chat. The big green stove needed wood, the floor sweeping with a rush brush, the big table setting or the Kenwood bowl licking.

“Ice cream was made and the preserves from the upstairs room emptied into it. The scullery filled up with pots and pans, plates and bowls. After dinner Gran and I would talk about everything we could think of and usually ended with a tea towel flick contest when taking off our aprons. The spare soap was put in the laundry cage for use next day. The kitchen was a place for women’s business where hands were never idle.

“Quiet was found in the room next door. It smelt of smoke from the big fireplace and the pipes and ashtrays sitting atop the smoking stand. Grandfather Poppy sat there. He read his books, smoked his pipe and sometimes even talked to me.

“He made people out of pipe cleaners and made them dance on his knee. He let me fill his pipe and listen to his large wooden radio. I was allowed to sit and read some of his books from inside the window seat, but only after he had approved them. The pack of cards was mine. ”

The joy of Aunt Daisy

P. Gilchrist arrived with her family to a “run-down house” in Richardson Rd in Easter 1951. She remembers: “We moved in with two suitcases of clothes, a gate-legged table, four chairs and a mattress. Such was the waiting time for furniture the rest was not ready for another five months.

P. Gilchrist arrived with her family to a “run-down house” in Richardson Rd in Easter 1951. She remembers: “We moved in with two suitcases of clothes, a gate-legged table, four chairs and a mattress. Such was the waiting time for furniture the rest was not ready for another five months.

“… Although the property needed a lot of work, our aim was to have our own home where, as long as we paid the mortgage and the rates, no one could put us out. We had a coal range, gas stove and a copper for washing. It was not for several years that regulations allowed us to put in electric water heating and about 1959-60 before telephones came into the houses in our area.

“…At first we had a small Bell radio, but later our pride and joy was a mantle radio with local and overseas wave bands. We often listened to Aunt Daisy, Friendly Road sessions, and Uncle Tom’s choir of Sankey Singers, Dossier on Demetrius, Palmolive Treasure House, Top of the Charts and the Japanese House Boy. In the weekend mornings, there was a session called Kindergarten on Air, while Marina and the Happiness Club were popular in the afternoon. Once a week George Dean had a gardening session. We could listen to the news from YA stations and music and sport from several, plus school for correspondence students. Where did the choices stop? Radio was our entertainment.”

The downside of endless fruit

Mrs Greeney (Potter) arrived in Mt Albert in 1949 when she was four-and-a-half, and she remembers: “Our milk was delivered from a pail by Mr Long, on his horse and cart. The horse knew every stop and there were enough gardeners in the street, eager to clean up after the horse!

“Most houses had venerable gardens and all had fruit vines or trees.

My friend Din and I would end up with stomach aches from the green apples and peaches we ate. The baker came to the back door every morning with a basket of loaves from which my mother would make her choice.

“…We didn’t have a phone or television, but we had a radiogram my father had built and evenings were spent either with the family playing 78 records of with my sister listening to serials or, if it was my turn, dancing to the popular tunes of the day.”

Hi-heels and halter-necks

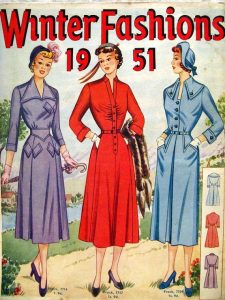

Shirley Henderson remembers: “During the late 40s and 50s, life and industry started to get back to normal and imports were resumed. All of a sudden, after the lean, sparse war years, an irresistible array of colourful fabrics appeared in the shops and ‘the new look’ was born. Swirly full-skirted frocks – some with stiffened net underplays – were the order of the day. Swing coats (with lots of gores, or cut-on-the-cross at the back fell into soft folds) were cape-like but gave an “A-line” effect as well. Nifty two-piece suits, some with nipped-in waists and peplum-styled jackets were considered very smart. Halter-necks, fischu and off-the-shoulder styles were popular for evening wear and sunfrocks were bright and colourful.

Shirley Henderson remembers: “During the late 40s and 50s, life and industry started to get back to normal and imports were resumed. All of a sudden, after the lean, sparse war years, an irresistible array of colourful fabrics appeared in the shops and ‘the new look’ was born. Swirly full-skirted frocks – some with stiffened net underplays – were the order of the day. Swing coats (with lots of gores, or cut-on-the-cross at the back fell into soft folds) were cape-like but gave an “A-line” effect as well. Nifty two-piece suits, some with nipped-in waists and peplum-styled jackets were considered very smart. Halter-necks, fischu and off-the-shoulder styles were popular for evening wear and sunfrocks were bright and colourful.

“Women still dressed up to go to town, and the outfits were not complete without matching gloves, handbag, shoes – and maybe a pert little hat! Plain classic court shoes were worn for ‘best’, good brogues for walking, sandals or sand shoes for the beach.

“Bikinis as such hadn’t quite arrived in the 1940s and 1950s, but a decorous two-piece bathing suit was available – usually in a type of stretch chenille. That exotic fabric, called jersey silk, made its appearance in an amazing array of flamboyant colours. It didn’t crease and could be simply rolled up and put away in a drawer, even a favourite cocktail dress! In the late 50s, a fashion conscious woman wouldn’t be without a pair of stiletto heeled gro-calf shoes. Never mind the inlaid linoleum, the Feltex carpet or the polished wooden floor. The shoes flattered the legs and offset the swirly mid-calf length skirts!”

Saturday afternoon at the flicks

Barbara Hyde (Thompson) remembers her times in the 40s and 50s at the family home in New North Rd: “My brother Les and I liked the Saturday afternoon pictures at the De Luxe theatre.

My favourites are the westerns and there was always a thunderous stamp of approval when the “baddies” were shot or an Indian/cowboy race was on.

“I recall a weekly serial called the Rattler, an evil fellow completely hooded and cloaked in black. It gave me the terrors and I’d crouch behind the seat in front peeking through a partially opened hand to see if it were OK to sit back in my seat! Those Lassie films were tear jerker and I’d sob all the way home, but yet still go back when another Lassie episode was screened.

Timing the roast to the word of God

Ian Kemp was born in 1926 in the Rob Roy St that his parents had built two years earlier. He remembers: “For years there was a Sunday morning routine in our family. Dad washed the car, mother prepared the Sunday roast dinner, my sister and I busied ourselves with household chores, while our maternal grandfather, who lived with us, set off down Alberton Ave to walk to church – the Baptist Tabernacle 5km away in Queen St.

“Meanwhile the rest of us donned our best clothes for church, piled into the car and followed Grandpa till we caught up with him along New North Rd, sometimes as far as Eden Terrace.

“As much a part of the Sunday morning routine as anything else was the weekly fill up at the benzine pumps at Kingsland on the way to church. The angled entry into the two pumps was just as awkward as it is at the same petrol station today (now part of the BP syndicate)…That benzine station was about the half way point between home and church. Depending on whether we had met grandpa before we reached the benzine station or after we had left it, we were able to judge how far he had walked or how late we had left home.

“Either way, we usually reached church in time, though often not a little frazzled. In the years since I have often wondered how much attention mother ever gave to a Sunday morning sermon, knowing that her prized roast in the oven was likely to burn if the preacher should exceed the expected time limit.”

Kidneys, liver… and chewing gum

Pat Pound was born in in 1939 and remembers the war years – and the American servicemen who were invited into the family home: “During this time there was severe food rationing in New Zealand…we had rationing coupons for things like meat, clothing, stocking, cigarettes, tea and coffee – and I think, also eggs and flour.

“I was the coupon kid who, a day a week, went around the various neighbours and swapped the coupons we could do without for the ones the neighbours didn’t want.

“I was the coupon kid who, a day a week, went around the various neighbours and swapped the coupons we could do without for the ones the neighbours didn’t want.

“…There wasn’t any good meat – it all went overseas for ‘our boys’. All that could be bought – only with coupons – was mostly mince (fatty as!) and stewing chops (neck) and shin meat. We always ate meat every meal but only because we ate offal and that didn’t require coupons – brains, kidneys, liver, sweetbreads etc. I never used to think of them as yukky and still love them to this day. My dad went fishing, always successfully, and we would go out to Pt Chev reef at low tide for mussels, crayfish, and always dug up cockles on the way back to shore.

“…When the Yanks were invited to our home, these lonely boys would arrive with Wrigley chewing gum (in flat slabs) and Lifesavers and barley sugars and, on one memorable occasion, a big Dixie of ice cream – only to find nobody had a refrigerator let alone a freezer. The word went around the neighbourhood that the Pounds had ice cream and all the local kids came running with their plate and spoon. Yummy!”

How an onion eased the pain

Colin Whyte was born in 1932 and remembers tough times at school, and those Americans: “We sat on a wooden plank, behind the desk, two to a desk. We had to write with our left hand flat on the desk so that the teacher, who was walking around, looking at us at work, could give us a rap over the knuckles with the ruler he carried. Bad conduct brought us the strap, which was a leather yard piece about a foot long and three inches wide.

“The punishment was decided by how many strokes, six being the most I ever saw. [The victim] would stand in front of the class and told to hold his hand out. Then the teacher would hit his palm with the strap, allow him to jump around and try to ease the pain by putting his hand up his armpit etc and then hold out his hand again until the prescribed number of strokes had been delivered.

“Some boys carried an onion in their school bags which, if they got time before the strapping, they would secretly rub into their fingers and palm, believing the extra swelling and redness would result in fewer blows from the teacher.

“The crying boy, still in pain, would then walk back to his desk watched by his peers and continue his work.

“If there was continued misconduct or serious misdemeanours, the culprit would be caned. For this the boy would be sent to a teacher who did all the caning for the school (usually the assistant headmaster or a senior teacher). The boy was made to bend over a chair and the stipulated number of strokes was administered to his bottom with a cane.

“…I left school in form three on the day I turned 15. On the last day at Kowhai myself and the next largest boy settled who was the ‘toughest’ by having a fight. It had been building up for a while with exchanges of threats, glares etc, so it was eagerly anticipated by the other pupils. We were halfway through our contest and the blood was flowing, clothes torn and spectators cheering when a teacher burst through the crowd. The other boy looked at him and said, “It’s only a friendly fight, sir.” To which the teacher replied, “That’s all right then.” We looked at each and collapsed with laughter and were the best of friends from then on.

“…I left school in form three on the day I turned 15. On the last day at Kowhai myself and the next largest boy settled who was the ‘toughest’ by having a fight. It had been building up for a while with exchanges of threats, glares etc, so it was eagerly anticipated by the other pupils. We were halfway through our contest and the blood was flowing, clothes torn and spectators cheering when a teacher burst through the crowd. The other boy looked at him and said, “It’s only a friendly fight, sir.” To which the teacher replied, “That’s all right then.” We looked at each and collapsed with laughter and were the best of friends from then on.

“…The largest change in my life came from the American servicemen. We had been rationed in butter, meat, clothing, petrol and cream, and we hardly ever saw sweets or chocolate. All at once these Yanks were upon us and they had things enough to cajole our females into distraction.

“Silk stockings, sweets, scented soap, chewing gum, cigarettes and plenty of money. The poor old Kiwi male had no show!

“…All us children soon learnt that, “Got any gum, chum?” or “Could you let me have some fags?” usually got a favourable response and we often had two or three packets a day given to us. It got so bad that an American could not stand still for a few minutes without a child asking him for something.

“…The over-amorous Yanks became a nuisance as, any time of the day or night, any place at all, you could stumble over a couple. We gave up playing in the trees at Fowlds Park because of this, but we did learn the facts. After a while, the watching ceased to be fun, but if we recognised the girl we would tease her for fun!”

The war years at Gladstone

Ruth Williamson remembers time at Gladstone School during the Second World War: “The headmaster took the war very seriously. The Japanese didn’t seem too far away and it was rumoured that Darwin had been bombed. Trenches were dug in the field, enough to hold the whole school, should there be an air raid. Air raid practices were held and each child was issued with a little cotton bag on a draw string to hang around the neck, with name and address printed on it in indelible ink. It contained a cork and two wads of cotton wool.

“On hearing the air raid alert, we were to jump into the trench, bite on the cork and stuff the cotton wool into our ears. If we were on the way home from school we were to roll under a hedge or lie in the gutter.

“I don’t recall being at all worried by all this, though the prospects of jumping into a school trench with six inches of muddy water in it didn’t appeal too much.

“Dad set out to dig a family trench in the orchard and hadn’t dug far before he struck a lava cave. This made his work much easier, and we ended up with quite a fancy family trench, with roof and bunks, and shelves with stored food. It was a good place to play and I was sad when he filled it in after the war.

“When I was in standard two, my cousin was lost in the Irish Sea. This gave us a taste of the misery of war – it was no longer fun. I was sitting welding on a seat in the playground when I was noticed by Miss Tait, my teacher. She came and comforted me and everyone treated me with great kindness for the rest of that day.

“I remember that our dining room walls were covered in maps of Europe, and later of the Pacific. The family would cluster around the large console radios to hear Big Ben, then the BBC World News, to find out where our troops were and what was happening…when I was in standard three, the headmaster announced over the intercom, “The war is over!” and a great cheer went up all around the school.”

Serial times at the movies

An anonymous recollection of Saturday at the movies at Sandringham’s Mayfair Theatre in the 1950s: “Every Saturday we were all given a shilling – sixpence to get in, one penny each way on the tram and the rest for an ice block and lollies.

“We would stand in the queue eventually reaching the ticket box where Mr or Mrs Arnerich would give us a ticket to get in. George and his friend Adrian sorted us out at the top of the stairs. The lights would go out and they would be chasing the naughty kids with their torches until all was quiet. The Jaffas stopped rolling and we were all transported to the next chapter of the serial, Superman, Batman and Robin, or whatever.

“We would stand in the queue eventually reaching the ticket box where Mr or Mrs Arnerich would give us a ticket to get in. George and his friend Adrian sorted us out at the top of the stairs. The lights would go out and they would be chasing the naughty kids with their torches until all was quiet. The Jaffas stopped rolling and we were all transported to the next chapter of the serial, Superman, Batman and Robin, or whatever.

“Interval came and we all rushed down to the lolly shop. Mrs Faulster was there with her helpers (my friend and I for some time), selling sweets, ice cream and drinks, absolutely flat out for 15 minutes – then back to the major film…cowboys and Indians, Ma and Pa Kettle, Lauren and Hardy, the Marx Brothers. We weren’t fussy.”

Night carts and gas irons

Phyllis Mealing was born in 1912 and remembers the wide open spaces of the 1920s – and some of the household hazards: “When we came here, Wairere Ave was just a country road, a rough metal centre driveway with grass verges.

“The side with even numbered houses had a footpath the full length, but our side had a footpath for just a short distance – merely a track made through the grass by people walking on it, with the lower end covered by blackberry bushes.

“Meola Stream came across under New North Rd from the Baptist Church grounds, through rough stones and blackberry to Wairere Ave. After running along the side of the road, it veered across country to the rock cutting in Asquith Ave. It has since been diverted and covered over.

“The part by Wairere Ave was very pretty, with willow trees hanging over it. We used to go down and paddle in the water and pick watercress.

“…In the early 20s there was no sewerage or electricity. The houses were serviced by a night cart and we had a coal range and gas, which included a gas iron. It has been considered an update from the old irons, but I had put off as long as possible the ‘modern’ art of ironing. The gas flame came out the back – it seemed under my arm, with a flexible metal tube from the iron, but I cannot remember how it joined into the gas supply. I was very, very scared of that iron.

“So it was a great day when the electricity was turned on, even if, to start, it was one light hanging in the centre of each room. Then my parents bought an electric iron.

“…We belonged to the St Luke’s Church and, as well as being a part of the large congregation attracted there, we spent many happy hours in the church hall dancing to the beat of a piano and drums. We also danced at the Mt Albert Bowling Club and at Mt Albert Grammar School hall.

“Tennis was another popular recreation. Our family and close friends favoured Avalon Tennis Club and their friendly members took turns in loaning their homes for parties on match days. Private parties in homes were popular.

“Party games, competitions and of course the piano, helped by small instruments, did not worry our neighbours. They did not make the noise of the amplified recorded music and we know we enjoyed those parties because we remembered them next day. There was no drink, drugs or fighting at our parties.”

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

-

Recording our history is important. If you have a story to tell, don’t put it off. Write it now and send it! Just click here and paste it into our email link. Or email it direct to mtalbert.inc.co.nz

CAPTIONS (from top): A horse and its nose-bag, picture courtesy Mildenhall Collection, National Archives of Australia; Picking blackberries, picture courtesy National Library; Aunt Daisy at the microphone, picture courtesy Nga Taonga Sound-Vision Documentation Collection; Mt Albert’s Deluxe Picture Theatre in the 1960s, picture courtesy Auckland War Memorial Museum Collection; American servicemen brought chewing gum – and some left with New Zealand war brides, picture courtesy Alexander Turnbull Library.